It starts quietly. Weeks before the surgery. Scans. Blood work. Physical assessments. Neurological tests. The goal is precision. Surgeons need a roadmap before anything begins. Every structure has a function. Every millimeter matters. They use MRI, CT, angiography—each offering a layer of understanding. Before the patient enters the room, a plan exists in layers. Images, notes, and marked coordinates. All before the first incision.

The head is held still for a reason that has nothing to do with comfort

They use a head clamp. It looks intimidating. But it keeps everything motionless. Not slightly still—completely. The brain cannot shift during the operation. Not even slightly. Even a small tilt could mean missing a pathway or damaging something essential. The clamp locks into the table. It’s part of the structure now. One movement, one image. Nothing left to chance.

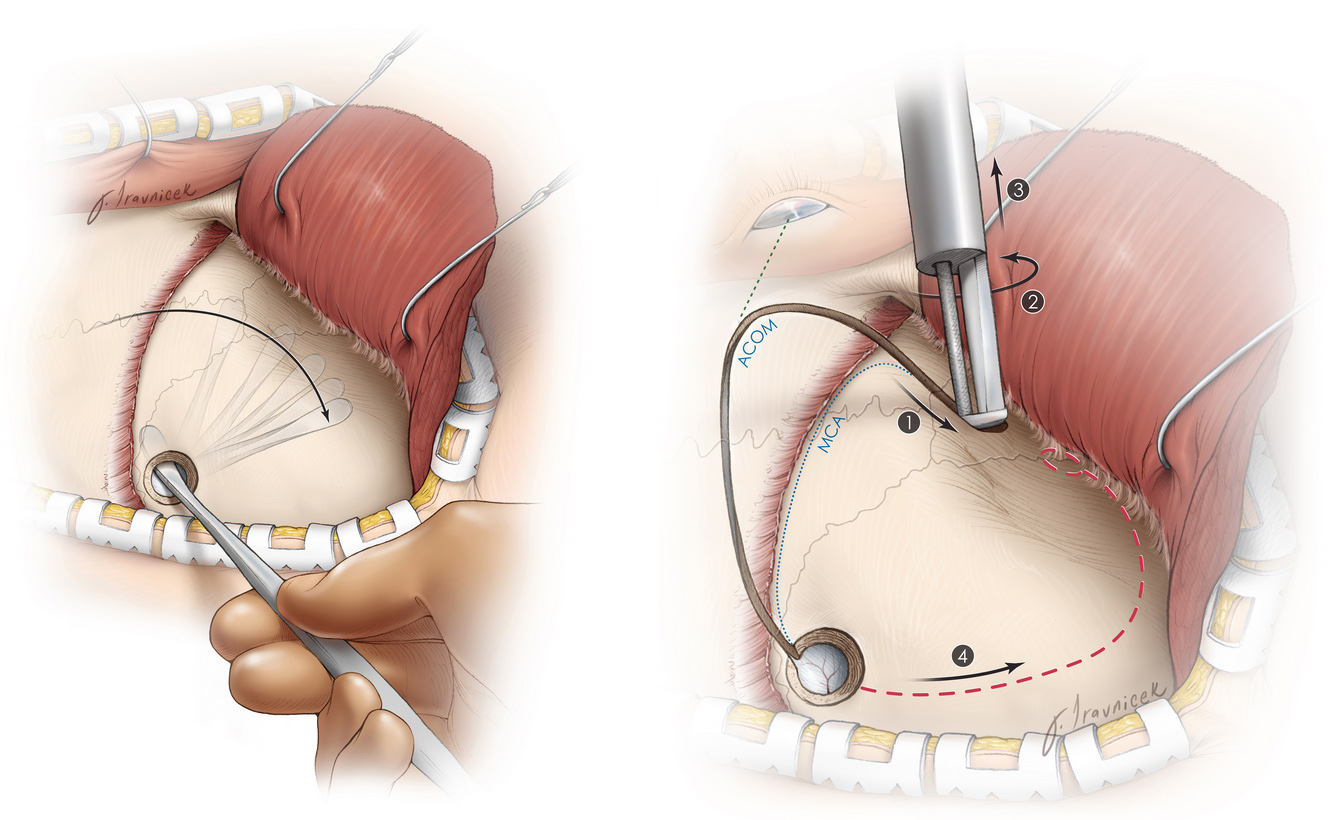

Scalp incisions follow a pattern that’s more geometric than I expected

They don’t just cut randomly. There’s a line. Sometimes curved. Sometimes straight. It depends on access. Surgeons plan around nerves. Vessels. Hairlines. Everything is calculated. The incision is clean. Controlled. They peel the skin back slowly. Sometimes with instruments. Sometimes with hands. Beneath it, the skull waits. Pale, smooth, motionless. That’s the next layer.

Removing a section of skull isn’t as violent as it sounds

They drill into bone. Not fast. Not aggressively. Circular motion. Slow pressure. The tool vibrates more than it cuts. Bone dust collects near the edges. Then they lift a piece—called a bone flap. They don’t discard it. It’s stored. Usually cold. Sterile. Waiting to be reattached later. The brain isn’t visible yet. Another layer waits.

The dura mater is the last barrier between the world and the brain

It’s a thin membrane. Slightly translucent. Almost grey. Surgeons cut it carefully. Not torn. They lift it like fabric. Tuck it gently. Once it’s folded back, the brain appears. Pulsing. Alive. Reactive. That moment always draws silence. Even in a room full of instruments, there’s a pause. Seeing the brain never becomes ordinary.

The brain doesn’t bleed like skin—it responds more slowly

Cuts in the brain don’t gush. They ooze. Tiny vessels seep. Surgeons use suction constantly. A thin, humming device. Blood obscures detail. And detail matters. They work around arteries. Drain fluid. Sometimes use small clips. Coagulate with heat. Every move controls risk. Bleeding isn’t stopped—it’s managed. Continuously. Carefully.

They use magnification more than you’d expect

Loupes. Microscopes. Screens. Everything gets closer. Amplified. They don’t just look with eyes. They enter visually. Depth and width shift. The tools feel huge on screen. But tiny in the hand. Sometimes both surgeon and assistant watch the same monitor. One moves. The other holds. Their movements look synchronized—because they must be.

The brain doesn’t feel pain, but everything around it does

That’s why the scalp, bone, and membranes are numbed or sedated. The brain itself has no pain receptors. That surprises most people. You could touch it. And the patient wouldn’t know. But pressure. Swelling. Inflammation—all cause pain afterward. They manage that before closing. Preventively. Because pain follows manipulation.

Tumors don’t always look different from brain tissue

Not every tumor is dramatic. Some look like surrounding tissue. Slightly different color. Texture. Consistency. Surgeons learn to feel with tools. The scalpel. The suction. Sometimes ultrasound helps. Sometimes dyes show contrast. But often, it’s practice. Experience. Judgment. That’s where training matters. Technique becomes intuition.

Not every brain surgery removes something—some create space or add support

Hydrocephalus requires a shunt. Aneurysms need clips. Epilepsy cases might involve disconnection. Not removal. Some surgeries are about pressure relief. Others place electrodes. Some insert stimulators. The brain isn’t always opened to cut something out. Sometimes it’s opened to make something possible. A reset. A shift. A start.

Replacing the bone is slower than taking it off

They retrieve the flap. Clean it. Sometimes reshape it slightly. Screws anchor it back in place. Titanium plates hold corners. Small ones. Hidden by hair later. The bone must match perfectly. Edges aligned. Movement locked out. If there’s swelling risk, they may delay replacement. Leave it out. That’s rare—but possible.

They close in layers—never all at once

First the dura. Sewn or clipped. Then the muscle. Then the skin. Each with different tools. Each layer is its own repair. Closure isn’t quick. It’s careful. They don’t rush the end. Every stitch matters. Every space sealed. Infection prevention begins before the wound is closed.

Waking up happens in stages, not suddenly

Recovery begins in the OR. Then the ICU. Eyes open slowly. Focus returns unevenly. Nurses test grip. Speech. Movement. Reflexes. Surgeons check pupil response. Orientation. It’s not about memory—it’s about presence. The first hours are delicate. Everyone waits for signs. Confirmation. Relief. Some reactions take days. Some take minutes.