The path following spinal fusion surgery is not a singular, clearly demarcated timeline, but rather a prolonged, multi-stage process demanding meticulous attention to detail and a fundamental shift in daily movement patterns. This major orthopedic intervention, designed to stabilize segments of the spine and alleviate chronic pain, initiates a significant biological event: the growth of bone across the surgical site to create a singular, immobile segment. The recovery is defined less by the disappearance of immediate post-operative discomfort and more by the disciplined adherence to restrictions that safeguard the delicate fusion process over many months. Understanding the complexities of this extended convalescence is paramount for patients seeking to achieve the desired long-term outcome, transitioning from initial dependence to a modified, yet often more functional, life.

The path following spinal fusion surgery is not a singular, clearly demarcated timeline, but rather a prolonged, multi-stage process demanding meticulous attention to detail

The initial days spent in the hospital setting immediately after the procedure are dominated by aggressive pain management and the re-establishment of basic functional mobility. “The path following spinal fusion surgery is not a singular, clearly demarcated timeline, but rather a prolonged, multi-stage process demanding meticulous attention to detail” highlights the non-linear nature of recovery. Patients awaken with expected soreness and stiffness around the incision, which is managed through a regimen of prescribed analgesics, often involving a combination of opioids for severe pain and other non-narcotic options. A critical early milestone is working with physical and occupational therapists to master the technique of ‘log-rolling’ to move in and out of bed, a vital maneuver to prevent detrimental twisting of the healing spine. Ambulation, often beginning within twenty-four hours, is strongly encouraged to promote circulation, reduce the risk of complications like pneumonia and blood clots, and gently reinforce the concept that movement, when controlled and proper, is a necessary component of healing. Discharge hinges not on the complete absence of pain, but on the control of pain using oral medication and the ability to safely manage self-care.

Patients awaken with expected soreness and stiffness around the incision, which is managed through a regimen of prescribed analgesics

The transition to home marks the commencement of the long, solitary phase of fusion growth, requiring unwavering compliance with the fundamental principles of spinal protection. “Patients awaken with expected soreness and stiffness around the incision, which is managed through a regimen of prescribed analgesics” emphasizes the importance of pain control. The cardinal restrictions—avoiding bending, lifting, and twisting (often summarized as ‘BLT’)—become the non-negotiable rules of daily existence for the first three to six months. Lifting is typically restricted to anything no heavier than ten to fifteen pounds, demanding creative modification of household tasks and often the assistance of family or friends. These restrictions are not arbitrary discomforts; they are critical safeguards against micro-movements that could jeopardize the integration of the bone graft. During this phase, the primary focus is not rehabilitation, but immobilization, giving the new bone a stable environment to consolidate.

The cardinal restrictions—avoiding bending, lifting, and twisting (often summarized as ‘BLT’)—become the non-negotiable rules of daily existence for the first three to six months.

For the first few weeks at home, managing energy depletion and maintaining a focus on incision care are paramount challenges. “The cardinal restrictions—avoiding bending, lifting, and twisting (often summarized as ‘BLT’)—become the non-negotiable rules of daily existence for the first three to six months” outlines the essential activity limitations. Surgical recovery, particularly from an operation of this magnitude, is an incredibly taxing process on the body’s resources, and a profound sense of fatigue often lingers far longer than the intense surgical pain. Rest, interspersed with frequent, short walks to maintain blood flow and prevent stiffness, is essential. The incision site must be meticulously monitored for signs of infection—specifically, escalating redness, persistent drainage, heat, or fever above a stipulated threshold. Prompt communication with the surgical team regarding any alarming symptom is a necessary safety measure, as complications like surgical site infection or nerve changes require immediate intervention.

Surgical recovery, particularly from an operation of this magnitude, is an incredibly taxing process on the body’s resources, and a profound sense of fatigue often lingers

Nutrition plays a surprisingly pivotal and direct role in optimizing the fusion process itself. “Surgical recovery, particularly from an operation of this magnitude, is an incredibly taxing process on the body’s resources, and a profound sense of fatigue often lingers” introduces the concept of long-lasting fatigue. Bone healing is a metabolically demanding process, requiring ample resources far beyond the immediate post-operative period. Adequate intake of lean proteins is essential for tissue repair and collagen matrix formation. Calcium and Vitamin D are fundamental for bone mineralization. Moreover, the inflammatory nature of the healing process can be modulated by a diet rich in anti-inflammatory components, such as Omega-3 fatty acids found in cold-water fish, and a high intake of fresh fruits and vegetables. Conversely, substances known to impede bone growth, notably nicotine from smoking, are an absolute contraindication, as their vasoconstrictive effects can severely compromise the blood supply necessary for successful fusion.

Nutrition plays a surprisingly pivotal and direct role in optimizing the fusion process itself.

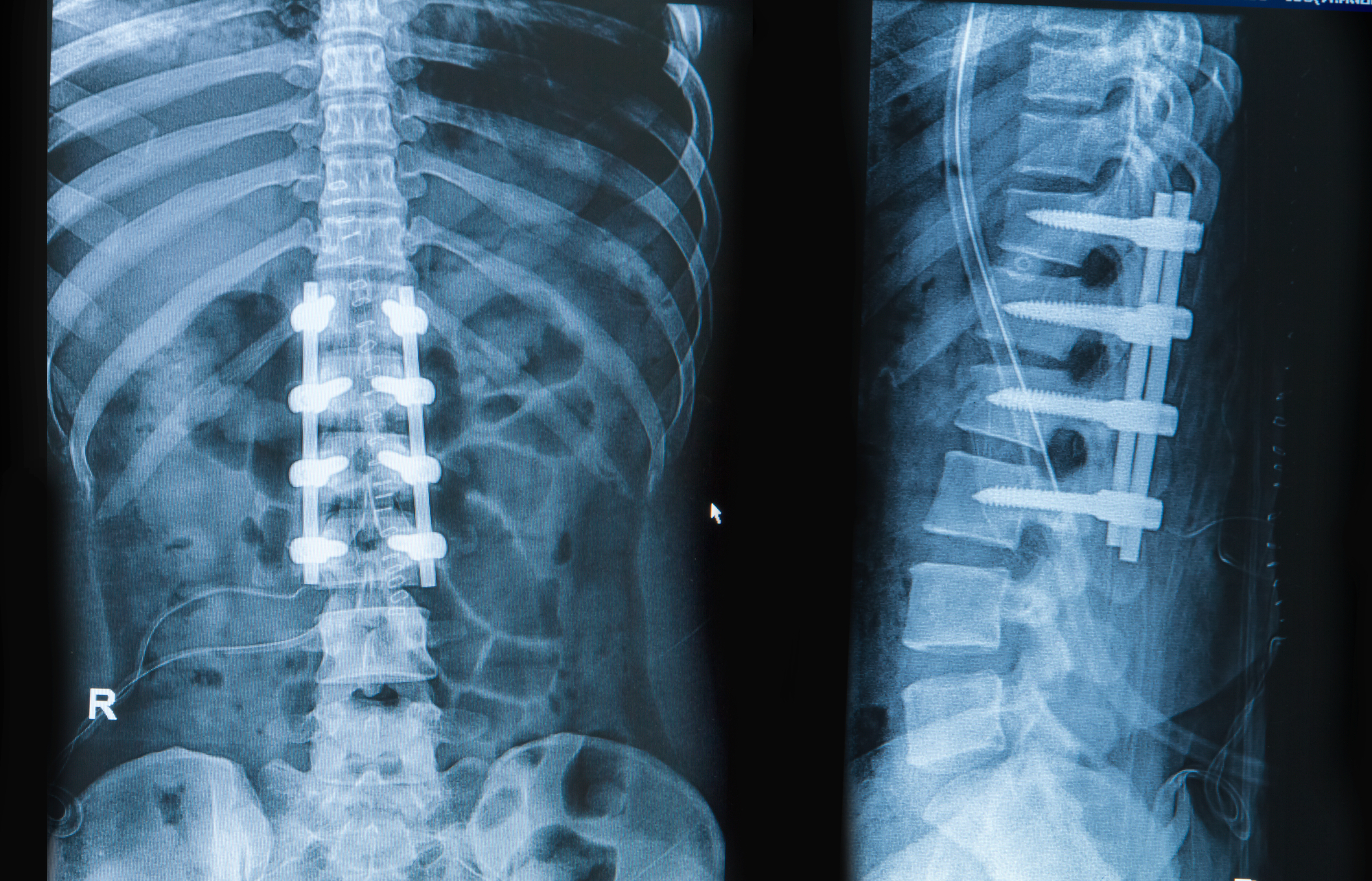

As the initial acute healing subsides, typically around the three-month mark, the focus begins to shift gradually toward regaining function and preparing for formal physical therapy. “Nutrition plays a surprisingly pivotal and direct role in optimizing the fusion process itself” underscores the link between diet and bone health. While the ‘BLT’ restrictions often remain, the intensity of movement increases, usually with the start of an outpatient physical therapy program. This is a highly individualized process, tailored to the patient’s fusion status—verified by X-rays—and specific surgical approach. Therapy initially concentrates on establishing core stability, improving gait mechanics, and performing gentle stretches to counteract the muscle atrophy and stiffness resulting from prolonged immobilization. The goal is to build a robust muscular corset around the spine to offload stress from the newly fused segments, a critical step toward long-term pain reduction and functional improvement.

As the initial acute healing subsides, typically around the three-month mark, the focus begins to shift gradually toward regaining function and preparing for formal physical therapy.

The six-to-twelve-month window after surgery is generally when the most dramatic return to functional activity occurs, provided the fusion is radiographically confirmed to be solid. “As the initial acute healing subsides, typically around the three-month mark, the focus begins to shift gradually toward regaining function and preparing for formal physical therapy” highlights the start of formal physical therapy. At this point, many patients are cleared to return to work, even those in jobs requiring light physical activity, and can begin to reincorporate recreational activities. However, the absence of movement in the fused segment necessitates a permanent awareness of body mechanics to prevent excessive strain on the adjacent, unfused vertebral levels. This new biomechanical reality requires a conscious modification of everyday movements—using hips and knees to bend, pivoting the entire body rather than twisting the torso—to minimize the risk of developing adjacent segment disease over time, a common long-term complication.

The six-to-twelve-month window after surgery is generally when the most dramatic return to functional activity occurs

Long-term life after spinal fusion is fundamentally a life of disciplined self-management, even after complete surgical healing, which can take up to eighteen months or more. “The six-to-twelve-month window after surgery is generally when the most dramatic return to functional activity occurs” refers to a critical milestone. While the debilitating pain that necessitated the surgery is often significantly reduced, the fused spine imposes a new set of constraints. High-impact activities, such as running, jumping, or contact sports, are often permanently discouraged to protect the hardware and the adjacent segments. The commitment to a lifelong, low-impact exercise regimen—swimming, walking, and core-strengthening exercises—becomes a necessary element of preventing future spinal issues. This sustained effort ensures the strength of the supporting musculature remains adequate to bear the load that the now-rigid spine can no longer fully absorb.

High-impact activities, such as running, jumping, or contact sports, are often permanently discouraged to protect the hardware and the adjacent segments.

The emotional and psychological aspect of this recovery cannot be underestimated, a reality that often goes unaddressed in clinical discussions focused solely on physical healing. “High-impact activities, such as running, jumping, or contact sports, are often permanently discouraged to protect the hardware and the adjacent segments” stresses the need for long-term activity modifications. The protracted timeline, the dependence on others, and the frustration of activity restrictions can lead to periods of profound mood fluctuation, including anxiety and depression. Acknowledging this emotional toll as a normal part of the process and seeking psychological support, whether through formal therapy or joining patient support groups, is as vital as the physical rehabilitation itself. Successfully navigating the emotional labyrinth ensures that the patient emerges from the recovery period not only physically stabilized but also psychologically resilient and prepared for the long-term adjustments required.

A part of the process and seeking psychological support, whether through formal therapy or joining patient support groups, is as vital as the physical rehabilitation itself.

Ultimately, the measure of success following spinal fusion surgery is not the date of discharge, but the sustained, disciplined adaptation to a new way of moving and living. The procedure offers the opportunity to replace incapacitating instability with robust, pain-free support, but this potential is realized only through consistent adherence to the rigorous, multi-stage recovery protocol. This commitment extends years beyond the operating room, requiring the patient to become an expert in their own modified biomechanics and a tireless advocate for their long-term spinal health.